Ross McGill

Three Questions You Need to Ask If You Invest in US Securities

TConsult does not give of offer tax, legal or investment advice. This material is for educational purposes only.

If you want to invest in US-listed stocks or receiving US-sourced dividends, what you don’t know can cost you—sometimes as much as 30% in withholding tax. The rules that govern how much tax is withheld on your investment income are complex, involving international treaties, IRS forms, and the legal status of your financial institution. In this post, we’ll walk you through three essential questions every non-US investor should ask to avoid unnecessary tax leakage and make sure they’re set up to benefit from reduced treaty rates—if eligible.

Question 1

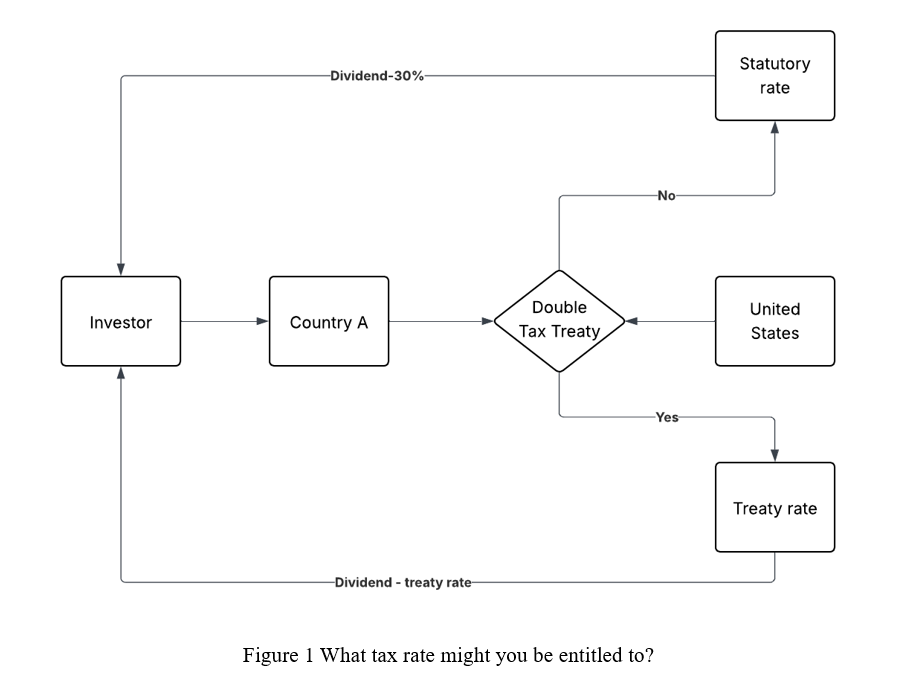

Are you a tax resident of a country that has a double treaty with the US?

If yes, then you may want to claim the benefits of that tax treaty. This would mean that any US dividends paid to you could be taxed at the treaty rate (often 10,15 or 25%) instead of the much higher statutory rate of 30%.

This is normally done by submitting a US Form W-8 to your financial institution. There are 5 types of W-8, and the one you complete will depend on your legal form. If you’re a natural person, then it will likely be a W-8BEN, part III of which is a claim for treaty benefits, which is made under penalty of perjury. If your account is in the name of a company, you will probably need a W-8BEN-E. You would normally be asked for a W-8 form when you first open an account at a financial institution irrespective of whether you expect or intend to invest in the US markets.

Question 2

What kind of institution is your account with?

Is the financial institution you have an account with a QI or an NQI?

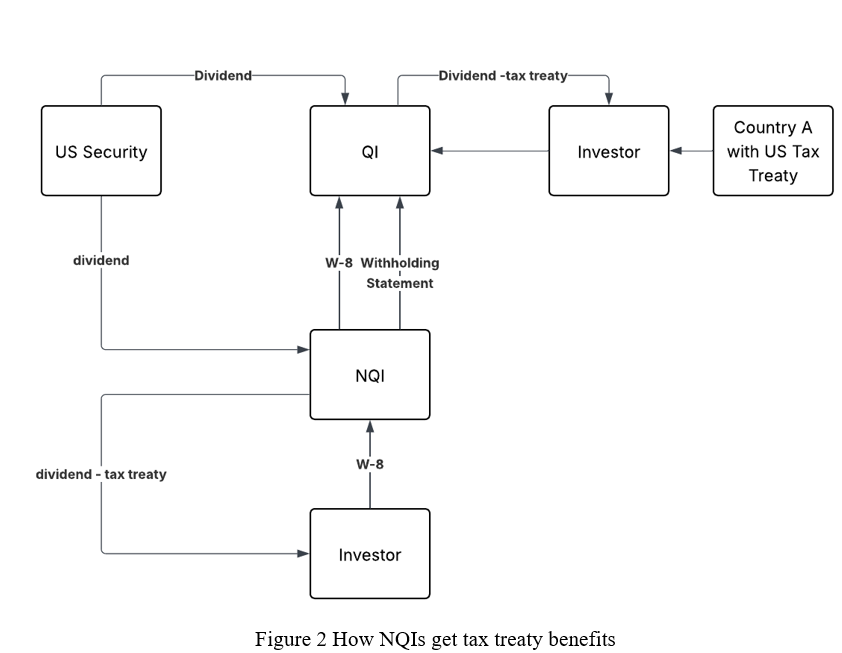

A Qualified Intermediary (or QI) has signed an agreement with the IRS that allows them to grant you tax treaty benefits. If you’re not sure whether your financial institution is a QI, you can find a complete list of QIs on the IRS website.

A Non-Qualified Intermediary (or NQI) doesn’t have an agreement with the IRS. Why is this important? Because it means they won’t be able to grant those tax treaty benefit to you. Only a QI can do that. So even if you’re a tax resident in a treaty jurisdiction and you’ve claimed the benefit of the treaty on Form W-8, you won’t get that benefit unless your account is with a QI. Instead, Uncle Sam will take 30%.

There’s one, and only one situation where you can get treaty benefits even if your account is with an NQI, and that’s if the NQI chooses to disclose you as an investor to a QI. NQIs who use this method are called Disclosing NQIs. They will pass your W-8 to their QI counterparty further up the payment chain, along with a withholding statement that allocated the payment to the W-8. This is done so that the QI can make payments at the treaty rate, rather than the 30%. It looks a little like this:

It’s important to not go assuming that just because you presented a Form W-8 with a claim of treaty benefits on it, that they will automatically be granted. Whether you get the benefit to a double tax treaty doesn’t just depend on the Form W-8. It also depends on how the IRS sees the status of your financial institution, and the policies of your financial institution with other financial institutions in the chain of payment.

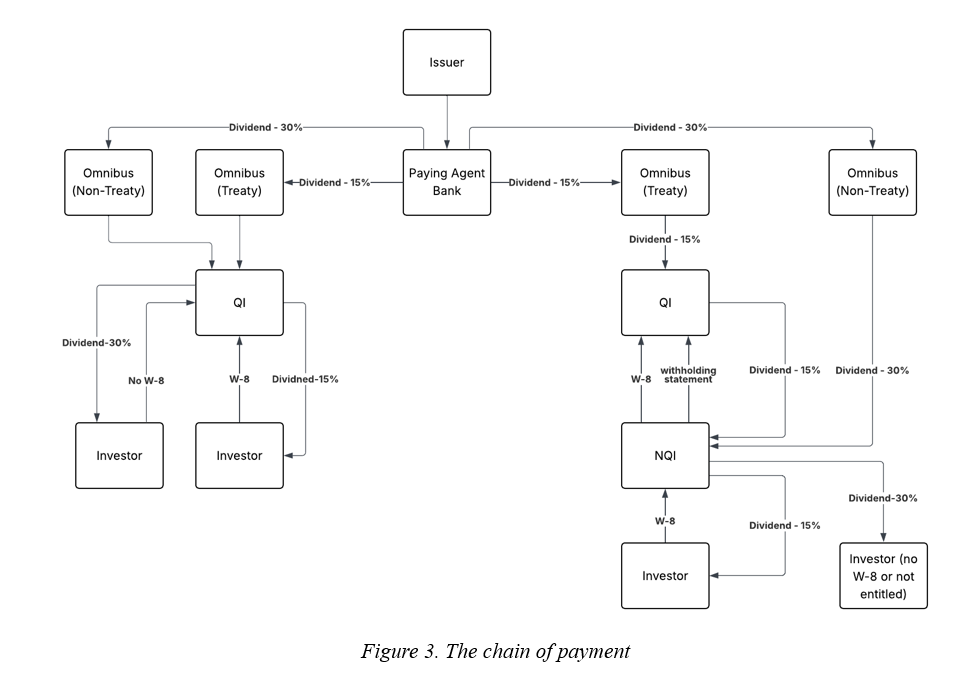

A Brief Aside

‘But what’s a chain of payment?’ I hear you cry. Well, if you buy shares in a US listed corporation, that corporation is known as an ‘Issuer’. When the Issuer decided to distribute a dividend, they typically use a Us financial institution called a ‘US paying agent’. The paying agent has customers who are also financial institutions, many of whom will be located outside of the US. These non-US financial institutions will have direct clients (investors of their own) as well as accounts of other non-US financial institutions. Outside the Us, all financial institutions will be either QIs or NQIs, so you and your financial account end up, at some point, in that chain of payment.

But here’s the thing to understand. Your account and US assets aren’t held separately from everyone else’s. Typically, they’re co-mingled into what are called ‘omnibus accounts. This method is much cheaper, and it’s easier for a financial institution to operate a small number of omnibus accounts than to open a separate account for each of their clients. In fact, often a QI will have two omnibus accounts – a treaty account and a non-treaty account. If you have a valid W-8 on file with them, they’ll put your US assets into the omnibus account marked for treaty taxation at, say 15%. If you don’t provide a W-8 or don’t claim tax treaty benefit on it, then your US assets will be put into the omnibus account marked for taxation at the statutory 30%. When the paying agent receives the gross payment from the Issuer, they will pay the omnibus accounts of their customers based on the tax rate allocated to that omnibus account. The result looks like this:

Once the funds are in the account, each of those financial institutions then pays their customer’s omnibus accounts, and so on and so on until the last financial institution is paying its direct customer. In this chain of payment, only a QI knows the identity of the person being paid.

Lessons to Learn

- Just because you are resident in a country with a double tax treaty with the US does not mean that you’ll automatically get the benefit of lower taxes on US sourced passive income, like dividends or interest. A QI can grant treaty benefits to a customer without a W-8, but they then become liable for any errors. So most require the W-8 Form.

- Just because you’ve provided a W-8 form with a claim of treaty benefits on it does not mean that you’ll automatically get the benefit of lower taxed on US sourced passive income. That will depend on whether your financial institution is a QI or an NQI. If they’re an NQI, they’ll need to be a disclosing NQI before they can get you those treaty benefits. Before you open a trading account, make sure you know the status of the financial intuition. QI is the best option, disclosing NQI is next best, and non-disclosing NQI is worst.

Question 3

Can I claim anything back directly from the IRS if my financial institution over-withholds tax?

Only in very limited circumstances.

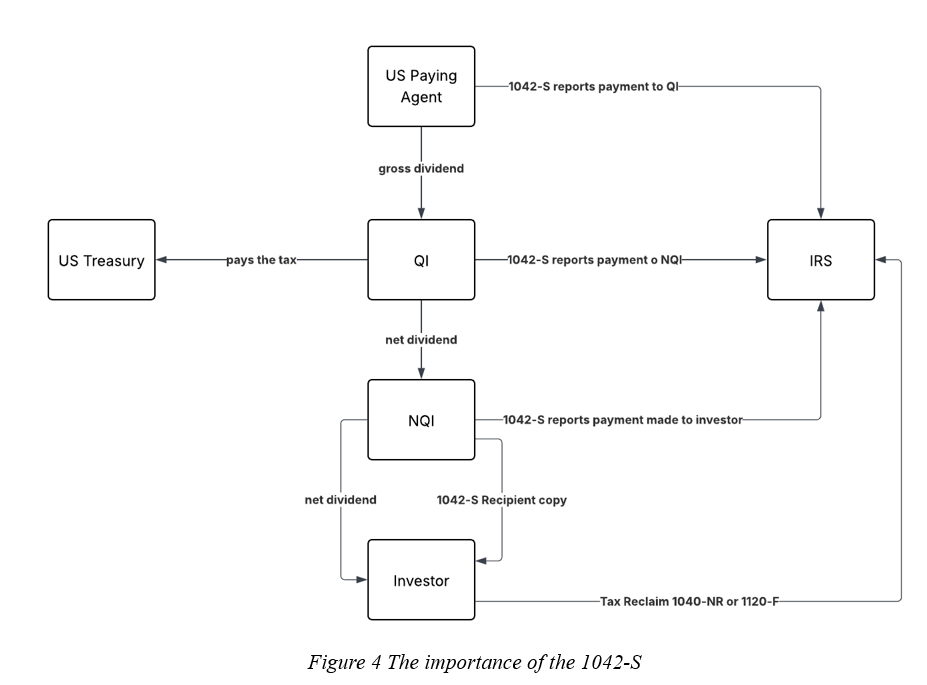

It all comes down to reporting. While you’re getting all of these US dividends, someone at the top of that chain is paying the tax to the US Treasury so that you’re getting the net dividend. The financial institutions in the chain of payment are reporting these payments to the IRS every year (on Forms 1042-S), and to each other. These are called ‘information returns’. QIs get to pool these returns so neither direct customers or individual payments are ever divulged to the IRS.

So, if you get taxed at 30% and think you’ve been over-withheld, you’ll first need to know whether your financial institution is a QI or an NQI.

If they’re a QI, you can ask them to refund the over-withheld tax. As I mentioned earlier, the QI Agreement gives QIs three different mechanisms to refund over-withheld tax to direct customers. If they don’t want to do any of those things, you can ask them to provide you specifically with a recipient copy of a 1042-S. The QI Agreement states that if you ask for one, they have to provide you with one. You can then use that 1042-S as evidence for over-withholding in a claim to the IRS. QIs really don’t like this solution, because it gives them a huge amount of work to do, as well as filing amended reports to the IRS.

But, if you know your stuff, you’ll often be able to get them to refund you. One thing to remember, the amount of tax you pay is based on the documentation they had on hand at the time the payment was made. So, if you had not made a treaty claim or didn’t provide a W-8, the correct rate of tax would have been 30%. If you try to reverse justify a claim of treaty benefits, that probably won’t work. But sometimes, if you can provide a W-8 with something called an affidavit of unchanged status (which effectively backdates the W-8 to a prior date), they might give you a refund.

If they’re an NQI however, then you should have received a recipient copy of your 1042-Ss either directly from your NQI financial institution, or from the QI institution that your details were disclosed to. Either way, the 1042-S is your evidence of over-withholding, and your name will be on it. That opens the door to submit a claim to the IRS to reclaim some of that withheld tax.

The process looks something like this:

You might think that’s the final basis of your claim to the IRS, but you’d be wrong. The IRS will want to be able to reconcile your claim to the actual tax payment that someone in the payment chain made to the US Treasury. And remember those omnibus accounts? The ones the financial intermediaries have been using to co-mingle your US assets with all their other customer’s US assets?

Well, for your claim to be successful you’ll not only need the 1042-S form and the claim form (1040-NR for an individual, and 1120-F for a corporation), you’ll also need to be able to recreate the payment chain. You do this by getting a letter from each financial institution in the chain to confirm your assets were in an omnibus account that was reported to the IRS on forms 1042-S. Finally, the institution that actually paid the tax as a deposit to the Treasury will need to be able to reconcile its deposit to an amount that was paid and reported to its customer. The chances you’ll get the cooperation from everyone in the payment chain to prove your claim is basically zero.

So, what’s the big lesson here?

The US is an incredibly complex securities market. So before you go opening financial accounts and trading US securities, make sure you know whether your chosen financial institution is a QI or NQI, and make sure you give them a W-8 form with a treaty claim (if applicable) when you open the account. Trying to back-track this stuff almost never works. If you’d like some help understanding the process, our team at TConsult are happy to help. Just get in touch with the team today

Ross is the founder and chairman of TConsult. He has spent over 26 years working in the withholding tax landscape with companies developing tax reclaim software and operating outsource tax reclamation services.

Ross not only sees the big picture but is also incredibly detail oriented. He can make even the most complex issues simple to understand. He has authored 10 books (including two second editions) on various aspects of tax, technology, and regulation in financial services, making him one of the leading authorities in the world of tax.